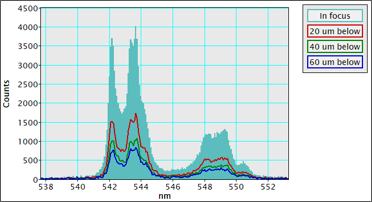

Anyone who has used an electron microscope or looked down an optical microscope realizes the ability to align and focus the (electron) optical system is critical to achieving the sharpest images. Cathodoluminescence (CL) microscopy experiments use both the electron optics of the scanning (transmission) electron microscope (SEM or STEM) and the light optics of the CL detector, and each must be aligned well. The two optical systems and samples must be co-aligned precisely to collect the sharpest CL maps, spectra, and emission patterns. As seen in the example spectrum (collected with the Monarc® system), misalignment of as few as tens of microns in a single axis significantly reduces performance. In other CL systems, a misalignment of just a few micrometers can prevent meaningful data from being collected.

In the following section, learn why optical alignments are so important and how to adjust a system to capture the best results. The system includes independent methods for Monarc users that automatically perform the alignment step without user input. The following section is useful for developing understanding, but proceed to the Monarc system's instructions for the practicalities of collecting optimized results.

SEM

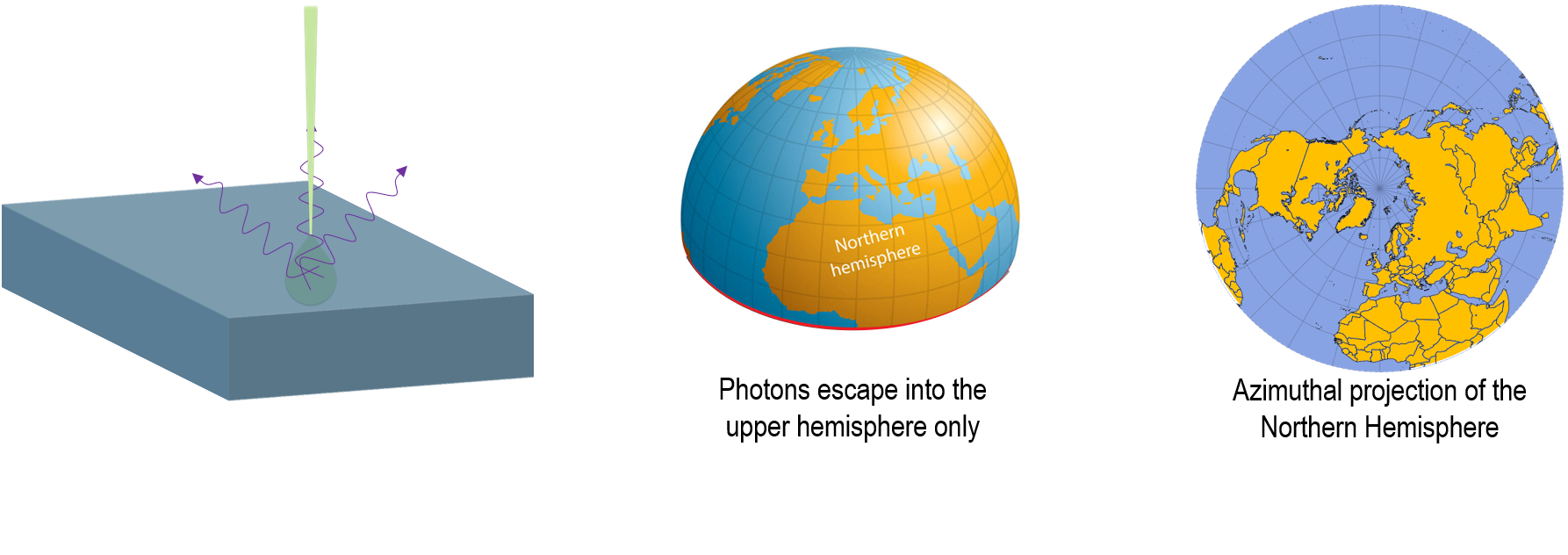

The electron beam generates light within our sample, e.g., within the interaction volume. In many specimens, these photons radiate isotropically, e.g., propagate with equal intensity in all directions. It may help to visualize this process by considering the light emission as a point source located at the center of the globe that radiates such that there is equal illumination at all points on the surface of the globe:

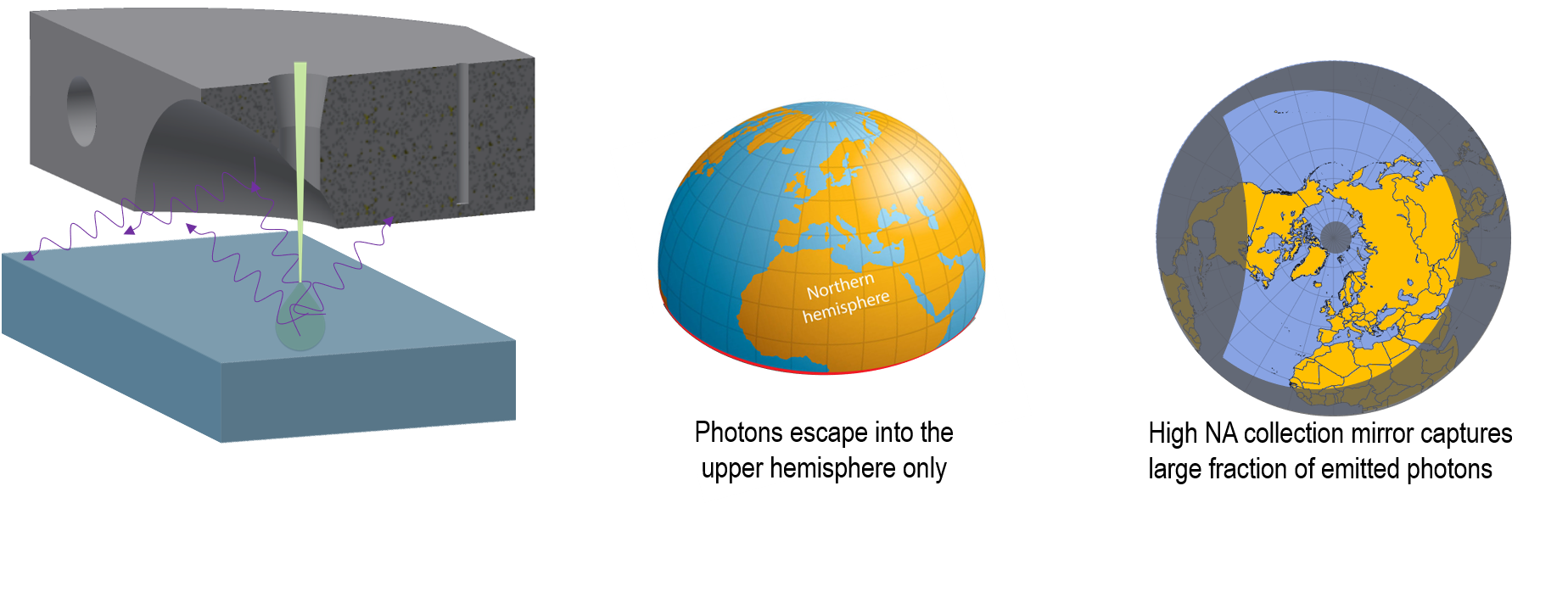

In some cases, the sample may absorb light before it ever escapes the specimen before it reflects and refracts at the sample's surface and is absorbed by the electron microscope stage or holder. For these reasons, in bulk specimens, it is more typical to consider that photons are emitted from the sample surface into the upper hemisphere only:

To have a detector with high sensitivity, it is of utmost importance to maximize the collection of photons. The preferred method is to use a high–NA (numerical aperture) collection mirror. A typical collection mirror is an off-axis paraboloid with an aperture to allow the electron beam to reach the specimen. When the sample is located at the parabola's focal point, ~85% of the emitted photons are collected and reflected into a collimated beam for further processing by an optical system. The polar plot of the Northern Hemisphere below illustrates the solid angle covered by a typical collection mirror:

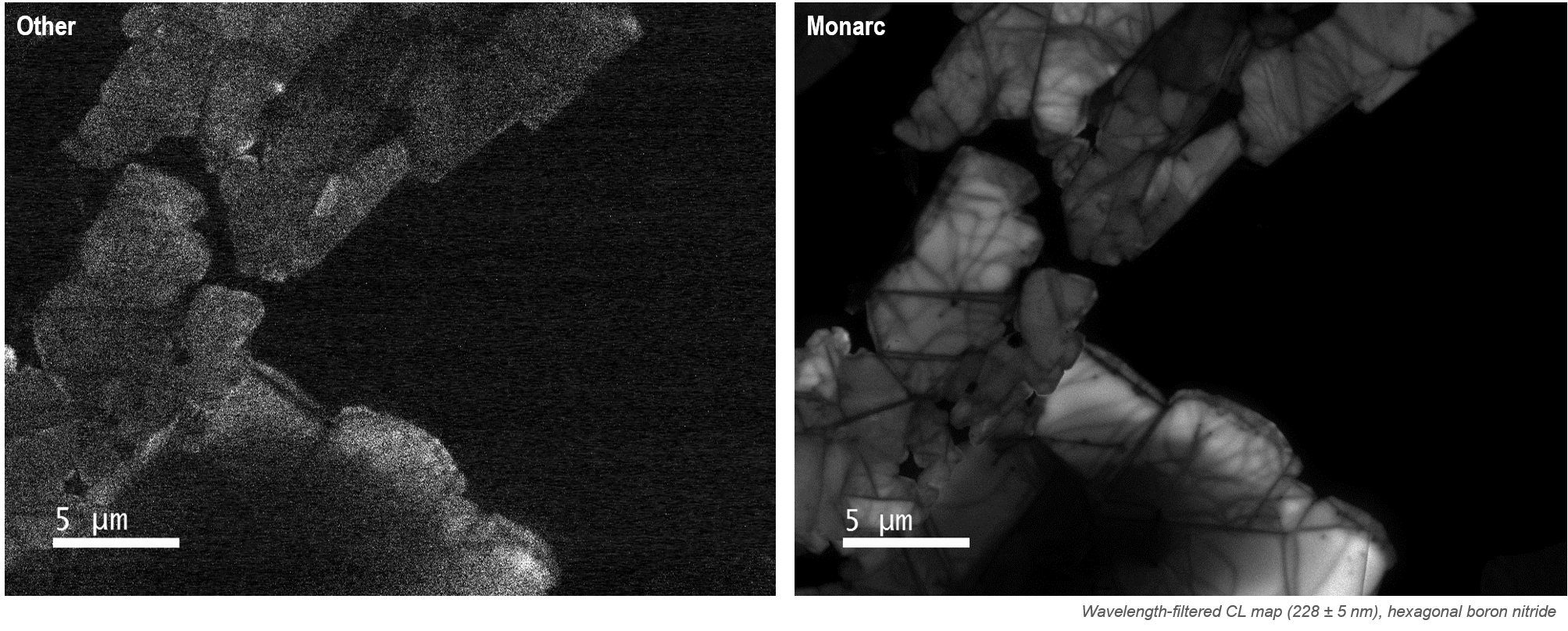

In these high-sensitivity systems, optical alignment becomes critical to capturing sharp maps, high-resolution spectra, and emission patterns. See, for example, comparative CL maps and a collection of spectra captured with varying degrees of misalignment in (just) one axis below:

In these unfiltered CL maps of hexagonal boron nitride, a misalignment of 100 μm (in the Z-axis) reduces the signal-to-noise ratio by a factor of 10, but with poor alignment in more than one axis, this could easily be a factor over 1000.

In the example of a CL spectrum shown at the top of the page, a 20 μm misalignment in the Z-axis reduces the collected signal by 50%, and at a misalignment of 60 μm, you can no longer resolve the double peak at 543 nm. In some analysis systems, a misalignment of just 5 μm may prevent data collection.

Basic alignment workflow

The basic steps to begin using a high-performance, mirror-based CL system appear to be straightforward:

-

Insert the collection mirror.

-

Center the collection mirror.

-

Set the sample at the operating working distance.

-

Focus on the SEM image.

-

Start your experiment.

We have already seen that it is important to align the SEM, CL system, and sample to within only a few micrometers. This sounds challenging enough, even before considering that you cannot directly observe the focal point of the collection mirror. The collection mirror of a CL system is designed with an aperture to allow the electron beam to reach the sample. Thus, the CL mirror's focal point is approximately at the center of the aperture. However, the exact location depends not only on the accuracy of the mirror itself but also on the alignment of the SEM's electron beam. When the SEM's accelerating voltage changes, the electron beam axis can shift, causing an apparent translation to the mirror's position and, if the optical axis of the SEM is not perpendicular, an apparent shift in the position of the focal point within the aperture.

With a specimen that emits light strongly and uniformly over hundreds of microns, performing this alignment manually after good operator training is relatively straightforward. Most, if not all, samples of interest for CL measurements exhibit significant spatial variation that makes this challenging or impossible even for expert users on many specimens.

Monarc MonoCL™/ChromaCL™ Vulcan®

Schematic ray diagram

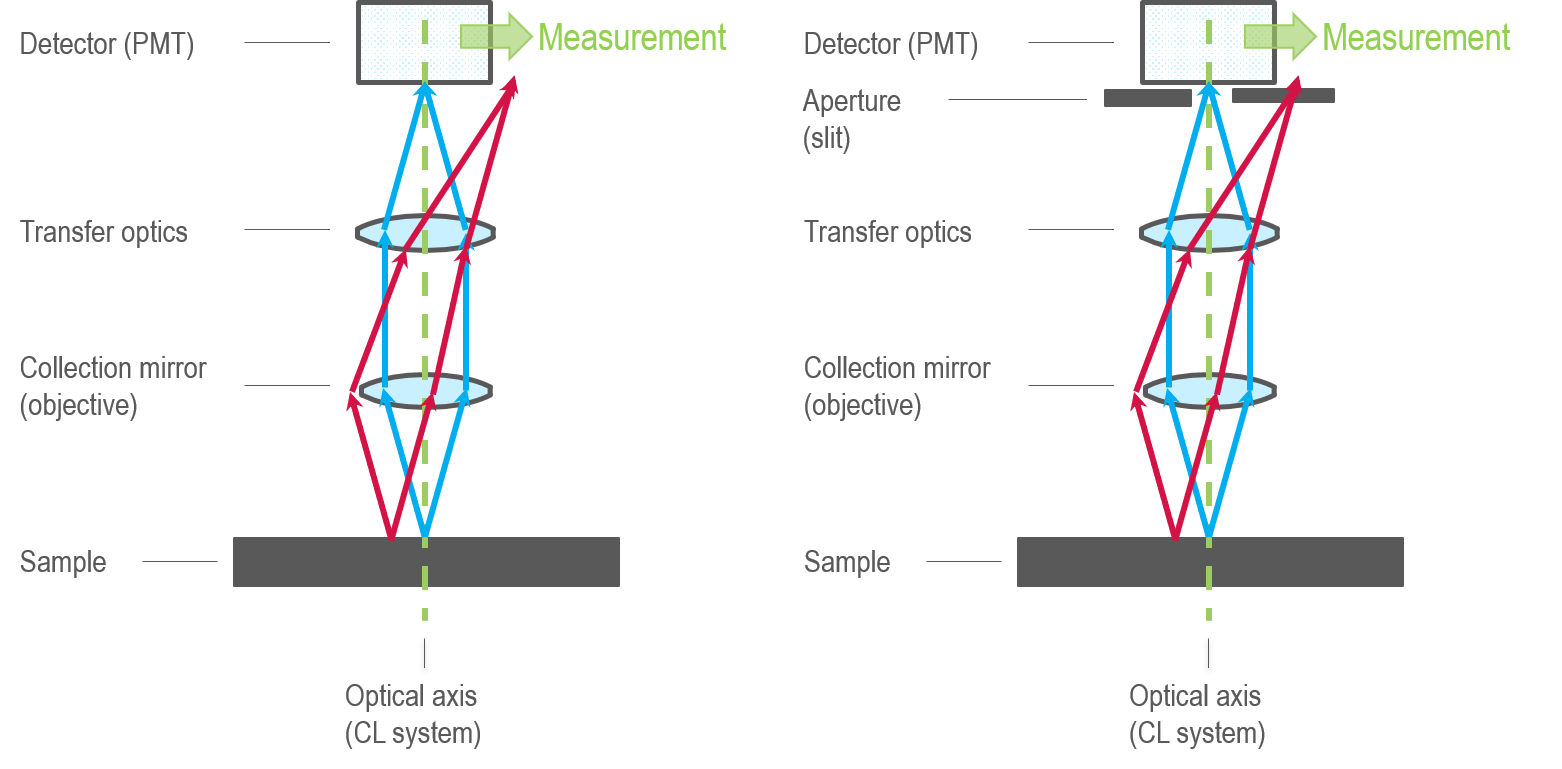

As we have seen, optical alignment is critical to collect optimal results (sharpest images or spectra or during the shortest acquisition time). In the following section, a simplified ray-trace diagram helps explain why alignment is so critical to many of the basic modes of operation of a CL system. One consequence of employing a collection mirror is that the alignment of the sample, the electron beam of the SEM, and the CL system becomes very important. Consider the simplified schematic of a CL detector shown below:

One can assume that light emerges from the sample at the location of the electron beam. If the sample and CL system are aligned well (blue lines), the light reflects from the collection mirror in a collimated ray bundle. For instance, the light rays travel parallel to transfer optics (a generalized term for the lenses, mirrors, or optical fibers used in the optical design). This transforms the ray bundle into a format suitable for the downstream analysis hardware. If the two systems are not aligned well around the CL system's focal point (red lines), the ray bundle no longer travels through the optical system in the intended manner, and few photons reach the downstream analysis hardware. This is even more critical when the light bundle must travel through an aperture, e.g., the entrance slit to a spectrograph, before reaching the detector. This has some important consequences:

- High fluence only when the sample is located at the CL system's focal point

- Low fluence when the beam is scanned out of the focal range of the optical system (vignetting) – A limited field of view in CL maps

- The field of view to capture CL spectra depends on the spectrograph's slit width unless you employ special transfer optics are employed (e.g., in the Monarc models 450 and 450.FS)

- Alignment must be sufficiently good not to destroy angular information in the image projected from the collecting mirror

TEM

The electron beam of a transmission electron microscope (TEM) generates light from within a sample. In many specimens, the photons radiate isotropically, e.g., propagate with equal intensity in all directions. The most efficient way to collect these emitted photons is to use large solid-angle mirrors positioned above and below the specimen, as in the holder of the Vulcan system. Light reflects from the mirrors and focuses on optical fibers that run out of the microscope to detect the hardware.

Proper optical alignment is critical in mirror-based systems. For example, a misalignment of just a few tens of micrometers can reduce the signal by 50% or more. With samples in the TEM typically emitting only weakly, precise optical alignment of a sample to the collection system is challenging and fraught with danger in the hands of inexperienced users unless, as with the Vulcan system, the system design guarantees optical alignment in most specimens.